Malchut

One of the deepest teachings of Kabbalah is also one of the simplest: that the world is not what it seems. As we have already explored, that which we experience as the world is actually a veil for the Infinite Oneness, the only thing that really is. Refracted through the various lenses of the sefirot, this “light” is the true structure of what is happening right now.

But what about what seems to be happening right now? A computer, a table, a person reading — are these illusion, maya in the words of another religious tradition?

In the Kabbalah’s understanding, the manifest world is also Divine, but it is — using the mythic language of the theosophical Kabbalah — in exile; in a state of apparent separation; in need of unity.

There’s a wise teaching that while the mind may know that all is one, the heart still experiences two. You and me; here and there; now and later — or before. And so the heart experiences a yearning which is sometimes sweet, oftentimes holy, and other times bitter and tinged with pain.

This yearning is also part of our reality. Our experience of separateness is part of our reality. And that which is present is not mere illusion: it is the Presence of the Divine, the shechinah, the tenth sefirah, also known as malchut, sovereignty.

Malchut completes the chain of the sefirot. If we imagine the first three sefirot to be an idea arising in the mind, the second three to be the stirrings in the heart as it weighs and evaluates it, and the third three to be the qualities of action that bring it into being, then malchut is its actual being; its manifestation. Yesod has gathered together all of the energies of creation — and then it creates. Malchut is the result.

In human terms, your malchut aspect corresponds to the fruits of your labor: that which actually happens out there in the world, once you’re finished willing and deciding and creating. In Jewish ethics, unlike in some other systems, malchut is the most important part; actions, not intentions, define moral character.

In Divine terms, malchut is the world that we experience, which is filled with the Shechinah, the Divine presence. Malchut is that aspect of the Divine which is totally immanent, absolutely here and now, closer to you even than your concept of “you.”

Consequently, malchut is also that aspect of God which — as expressed poetically, and in ways that would horrify some rationalist philosophers — experiences what we experience. When we experience joy, malchut experiences joy; when we experience sadness, malchut experiences sadness. Most radically, when people are oppressed, enslaved, or even exterminated — this is malchut’s experience as well.

The Feminine Aspect of God

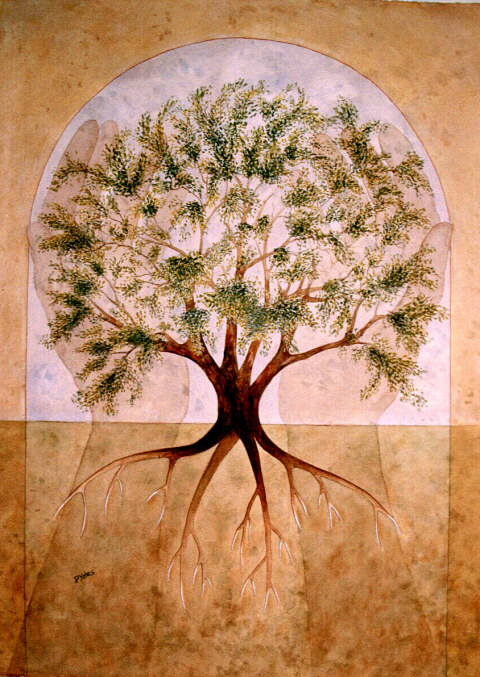

Malchut is not merely an abstract quality in the Kabbalah, however. It is also Shechinah, Presence, the revealed Divine face — and the Divine feminine. It is Shechinah who never leaves us, the Divine Feminine — in other systems understood as the Goddess — who is with us always and who is, like us sometimes, exiled from her Divine lover, the Holy One. Sefirotically, the Divine name “Holy One, Blessed be He” refers to Tiferet as expressed through Yesod — the active masculine principle, the “sky god” in primitive theology. Erotically, the great motion of the universe is the reunification of the masculine principle and the feminine one — yichud kudsha brich hu v’schechintei.

We will explore these themes in more depth later, but you can already see how scandalous Kabbalistic theology can sometimes seem. How different is this dynamic of Holy One and Shechinah from the ancient wedding of god and goddess, precisely the practices about which our ancestors were so concerned? And the more you know, the more “troubling” the situation becomes. Mystics are exhorted to experience this union sexually — with their wives, on Friday night in particular. Poems and prayers are composed to the Shechinah itself — for example, the many references to “Sabbath Queen” and “Sabbath Bride.” (Who do we think we are addressing in those prayers, anyway?) And the imagery of the Shechinah is, unabashedly, goddess-imagery: She is the Earth mating with the sky through the conduits of rain, She is the spirit in the trees, She is the ever-renewing cyclical flow of natural times and seasons.

Indeed, all this is very “troubling” if you have a fixed notion that God is male, or “genderless,” and that spirit and sex should be separate. But the Kabbalists do not have such notions. The Divine is male, and female. It is experienced through spirit and body — and also heart and mind. It is immanent and transcendent; perfect but also, from our perspective, constantly changing. Those faces of God with which we may be familiar from childhood — the angry judge, the man of war — are real faces. But so are the faces which have been suppressed for much of our history: the nurturing womb, the embracing All.

In order to understand this, I’d invite you to query just what polytheists and pagans think they’re doing anyway. Have you ever wondered? Let’s imagine a hypothetical member of a pre-industrial, perhaps even pre-literate society, someone who worships multiple gods and has a rich mythology of nature spirits, angels, demons, and so on. What is going on? Is this person just gravely mistaken? Deluded? Well, what about the hundreds of different religions around today? Are women who venerate the Virgin Mary wrong? Confused? Are over a billion Hindus, devoted to any number of different Divine beings (or manifestations) really worshipping something completely devoid of any reality?

Surely this cannot be the case experientially. A religion which offers no connection to spirit does not survive — as many religions are, indeed, failing to survive in some communities today. Clearly, the “primitive” person, the Kabbalist, and the devotees of different religions are experiencing something. We might disagree as to how that experience is interpreted and mythologized. Or we might not even disagree — we might see the language of myth and interpretation as precisely that: a means to conceptualize and frame into words that which is known but not articulated.

Some texts of the Kabbalah take precisely this view, even if it may strike us as surprisingly pluralistic. The Zohar, for example, understands even the despised idolatries of Ancient Canaan as merely imprecise in terminology. Asherah-worship, for example, is basically worship of the Shechinah — only with the mistaken notion that Asherah is really a separate being. Indeed, in one of the most shocking passages in the Zohar (brought to my attention by Rabbi Jill Hammer), Asherah is even a future name of Shechinah herself.

If the radical nature of these ideas is not resonating with you, imagine something closer to home. Imagine a text which says that Jesus Christ is but another name for Tiferet, or that Ganesh is just a name for Hod. Everyone’s on the right track, so to speak; it’s just in some of the theological details that they get confused.

Those texts, to my knowledge, do not exist. But the Zohar’s embrace of ancient paganism as being truthful, but subtly mistaken is equally radical. And, I think, much more plausible than any alternative I can think of. There are billions of people on the planet, all having authentic religious experiences in different religious language. Do we really believe that only the rationalist philosophers are accessing the truth of Being? Or can we open to the possibility that these non-rational, even pre-rational, modes of religious life are accessing something deep, primal, and true?

To be sure, the Kabbalah is not — as some would have us believe — a pagan practice of magic, myth, and sorcery. Until the last hundred years, it is only in the rarest, most heretical cases that Kabbalistic practice included colorful sexual rites, or syncretistic God/Goddess language. The Kabbalah may be aware of these energies, and honor them far more than does any other part of Judaism, but it is also conservative in nature. Traditional Kabbalah does not set aside the mitzvot, or Torah study, or the life of the pious. It remains a nomian, conservative Jewish phenomenon.

But if we are speaking of the Presence of God, then we are speaking of God as experienced — and that includes the gendered and eroticized images of Earth Goddess, princess, and bride. Across thousands of years and wide geographical expanses, peoples around the world have experienced the Divine as feminine. And the more some traditions have sought to erase Her, the more slyly She has persisted — sometimes in “Christmas Trees” or “Easter Eggs” (historically, both pagan symbols of the Goddess), sometimes even more subtly, as, for example, the object who sits behind a veil in every synagogue, wearing all her finery (silver crown, velvet dress), and then, at a certain point, she is undressed, and her two parchment legs are parted to reveal the secrets within. The Goddess is a nearly universal human experience, it would seem, and She remains in monotheism as a part of the unified One — albeit a part which is sometime in exile from the whole, and in need of unification.

(Incidentally, some critics have suggested that the Shechinah doctrine is itself historically connected to the cult of the Virgin in medieval Christianity. Most critics see this as the silly over-simplification that it is. If any sefirah is the Mother of God, it is Binah, not Shechinah — the “Higher Mother” which gives birth to the sefirotic Godhead. The concept of the Divine feminine is far larger than any particular manifestation of it.)

Malchut is probably the most important of the ten sefirot — remember, what’s higher on a Kabbalistic hierarchy is not more important than what is below — because She is closest to us. The great Kabbalistic project to restore unity and harmony in the Divine begins with unifying the immanent and the transcendent, or shamayim and aretz. We might also see that project as the essential work of traditional Judaism as a whole: bringing together the actual world in which we live with our ideal notions of truth, justice, and God. That project entails both an upward-pointing spiritual awareness, and a downward-pointing practical orientation; one aspect without the other is incomplete. And so we begin, and end, where we are.